Whenever there is a new film from the master of anarchistic cinema, Yorgos Lanthimos, I must remind myself to bring something to support my jaws into the theatre, for they are guaranteed to drop. It has happened multiple times, beginning with his first international film, The Lobster (2015), continuing to The Killing of Sacred Deer (2017), and finally, to a lesser extent, with The Favourite (2018). His latest entry, nominated for five and winner of two Golden Globe awards, is no exception save for one aspect: it is his best work to date.

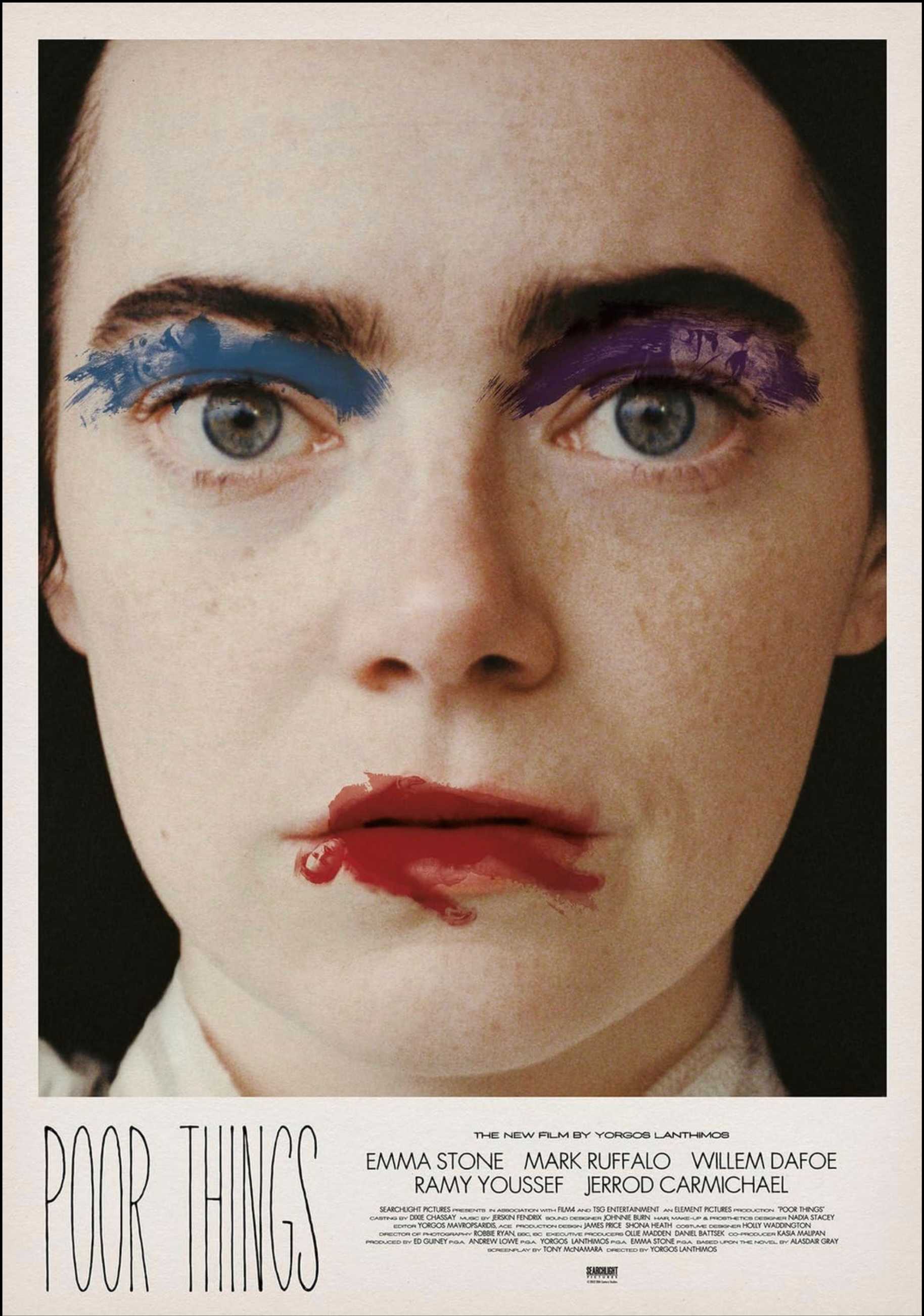

Poor Things (2023) follows the tale of Bella Baxter, portrayed by the ever-enchanting actress Emma Stone. Baxter, who in her earlier life went by the identity of a Victorian housewife, Victoria Blessington, ends up taking her own life, seemingly anxious and depressed about carrying a child for her homicidal paranoid husband, General Alexander Blessington (Christopher Abbott). To disturb the peacefulness of Bella's eternal sleep, she is discovered by her new father figure and something of a scientist himself, Godwin Baxter (Willem Dafoe), who goes on to reach Frankensteinian proportions by resurrecting poor Bella with electric current — after having implanted into her the brains of her unborn child. This tipping point effectively makes Bella both her mother and daughter — news she accepts without a faint heart.

Godwin himself is a victim of his father's sadistic scientific experiments that have left him with a horribly mutilated face and a malfunctioning digestive system repaired by his ingenious steampunk-ish machinery. What more apt way to pay homage to the dear old dad than to follow in his footsteps in revolting scientific exploration and to continue the twisted experiments on near-dead bodies? As Godwin bluntly puts it, science always comes first, which shows in his behaviour towards Bella. You wouldn't want your dear laboratory rat to escape, lest you need to create a new one.

As odd as it may sound, the experiments conducted on Bella to bring her back to life are less strange than many of the events that come to shape her life. We begin her journey from the captivity of her safe world — as described by Godwin, whom Bella admiringly calls God — at Godwin's estate. Early in the film, Bella can hardly act normally to a woman of her physical age and demonstrates the mental capability of a toddler by stuffing food in her mouth, trashing china, and inserting different objects inside her to reach happiness. Other Godwin's macabre creations accompany her throughout the house, such as a goose with a bulldog's head and a chicken with a pig's head.

To add to the perverse setting, we see Bella portrayed most of the film through a fisheye lens. First, in black and white to emphasise the dull life in captivity, and later on in entire vibrant colours after being rescued from this forsaken place and shown the joys of — to quote Bella — furious jumping by a devilishly charming lawyer with a meticulously cared moustache, Duncan Wedderburn (Mark Ruffalo). To Bella's chagrin, despite all its warmth and colour, the world outside is not indeed a paradise, as Godwin eagerly warned her. However, that doesn't stop her from exploring it with curiosity and the best intentions.

There is something highly sympathetic in Bella's coming-of-age journey as she travels through the different cities before returning to London to claim her place as the successor of Godwin's work. She discovers the pettiness of her lover Wedderburn, the horrible fate of sick children dying on the streets, the cruel violation at the hands of filthy men as a servant in a Parisian brothel, and eventually, the recurring sadistic possessiveness of her husband-general from a previous life to whose arms she briefly surrenders.

Yet, while these experiences truly shock her to the core, they do not keep her down. Inspirationally, Bella resurges from each adversity a better, stronger, more mature, and more intelligent version of herself. Whereas during the first scenes, we see Bella babbling and hitting people instead of shaking their hands, the final scene portrays Bella as a thoughtful and mature woman studying science and enjoying her newfound confidence and happiness. Indeed, throughout her two lives, none of the men in her journey can stifle the fire inside Bella or reduce her to an object to be put in place. This portrayal is an exemplary way of writing a strongly feminist narrative without underlying it in words nor cherishing how women are nothing more than helpless and oppressed victims of society.

Amidst Bella's strange journeys, we also enjoy a repertoire of comic reliefs sparked by her tendency for childlike honesty. Why, indeed, should you keep something in your mouth if it's revolting? Maybe that baby should be hit in the face if it insists on crying. The contrast in behaviour between the whimsical Bella and the people she engages with creates many of the most memorable scenes in the film that launched me and the audience into full-blown laughter.

Emma Stone's fantastic performance — arguably her best since La La Land (2016) — throws a genuine challenge for other actors to keep up. Willem Dafoe, who is no stranger to bizarre cinema thanks to films such as The Lighthouse (2019) and Antichrist (2009), delivers a complex portrayal close to Mary Shelley's world-famous tale of Doctor Frankenstein accomplishing to be terrifying and heartwarming at the same time. Mark Ruffalo, orders of magnitude better actor than you can judge from Marvel Cinematic Universe, shines as a drinking, swearing, and gambling wreck of a man whose primary satisfaction in life is manipulating people around him to his own ends.

From the supporting cast, two characters stand out. Swiney (Kathryn Hunter), the shady brothel hostess obsessed with biting skin and Harry Astley (Jerrod Carmichael), who leads Bella to witness the unfairness of life. Unfortunately, the same cannot be said of dreary Ramy Youssef, whose only function as Max McCandles, Godwin's assistant in crime, seems to remain vocally abashed by his acts of playing God. Surely, having spent a few days with Godwin, anyone would stop asking questions and either run away or forever commit to the madness.

Proof of an excellent musical score is the fact that often throughout the film, I paid attention to the shifts between the discordant tunes to more sombre melodies, which supported Bella's mood shifts and the slow buildup of the world around her. Audiovisually, the film is a delicacy I look forward to savouring many times, from the monochrome streets of London via overtly colourful alleys of Lisbon to cold and harsh Paris warmed only by lanterns in the brothel. Using painted sets is a bold directorial move that successfully gives the film its surreal Technicolor Hollywood style. Savouring is not an understatement due to the runtime of two and a half hours, which surprisingly does not contain a dull scene. It's a feat worthy of the film's many Best Film awards.

The mysterious, bizarre, dark, and wrenching work of Lanthimos' Poor Things paces between Wes Anderson's quirky lightheartedness and Lars Von Trier's pitch-black auteurism. By skillfully mixing elements from both, it reminds us that life is a bittersweet journey. Despite all the traumas, we can follow Bella and emerge victorious, assuming we take ownership of our lives. For our world ravaged by pandemics and wars, rare things spark brighter hope than this. If Poor Things is not a masterpiece, consider it a testament to the power of well-crafted cinema.